An Environmental History Magazine

An Official and Vernacular Description

of

Shifting Taskscapes in the Countries of Glacial Till

Beyond the Hundredth Meridian

Ryan Wanamaker, 2022

Part 1 Tattered and Entangled (Memories or Willful Amnesia of the Great American Desert)

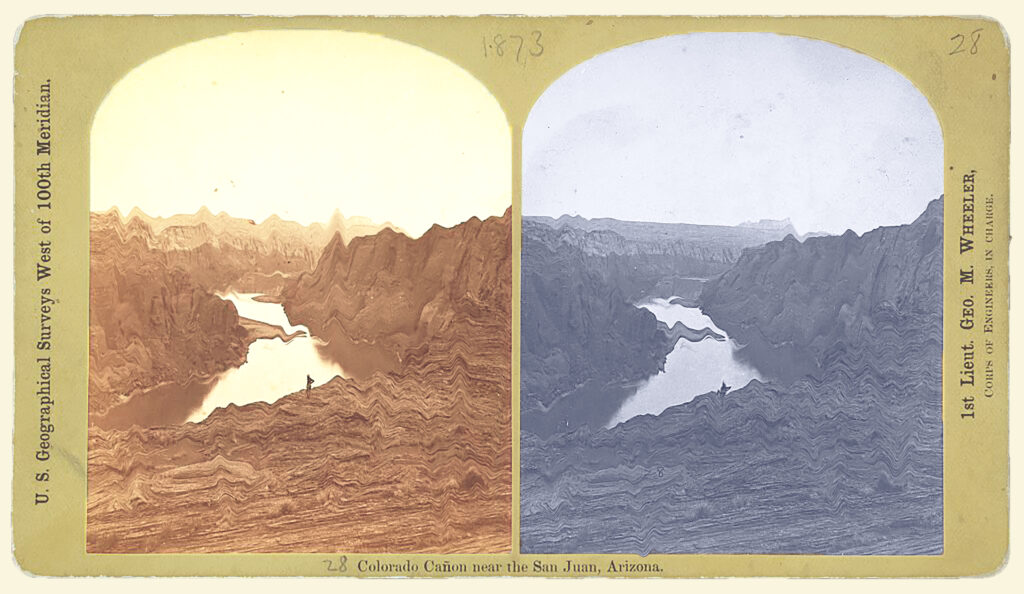

Decatur County, Kansas – bordered to the north by the state of Nebraska and to the west by Colorado – is about as close as one can get to being at the geographical center of the inaccurate and arbitrary boundaries of what many call the United States of America. Decatur lies on the western slopes of the Mississippi River Basin, the land mass’s great watershed. In 1878, John Wesley Powell identified the 100th meridian (longitudinal line) as an arbitrary but not completely inaccurate demarcation of the North American West. As Powell noticed, the 100th meridian signals the transition from the wetter, tallgrass prairie of the east, to the arid, shortgrass steppe and Rocky Mountains to the west.

According to Powell and his biographer Wallace Stegner aridity is the defining quality of the terrain west of the 100th meridian. Ever since the collapse and retreat of the Wisconsin icesheet around 10,000 years ago, what moisture exists west of the 100th meridian generally comes in the form of big mountain snowmelt and some isolated pockets in the rainforests of the northwest. The environmental histories – of bison herds, orographic uplift and rain shadows, of braided rivers and glacial till, of growth and decay, décrue and loess, corn, beans, squash, smallpox and genocide, American equines, mastodons, tundra, Eurasian equines, soils cultivated by Pawnee, Cheyenne, Comanche, Lakota, and their ancestors – were the ghosts, legacies, and ecological contingencies which European settler colonists would encounter in the mid-late 19th century.

Powell failed in his attempt to convince the western boosters and U.S. legislators of the contingencies and particularities of arid western ecologies and of the limits to growth – specifically that agricultural prospects and districts should be determined based on watersheds.1

The grasslands of North America, called the Great Plains, are a distinct ecosystem not amenable to methods and implements used to colonize regions east of the Mississippi River, which were more similar to the cleared forest lands of northern Europe. Later called the breadbasket and cowranch of the earth, the unbroken prairies were called the Great American Desert until the Civil War…The native [perennial] grasses held moisture and soil in place. Both were crucial under the conditions of low rainfall punctuated by violent downpours unknown in Europe or Eastern North America.2

Manifest destiny would impose blindness on – and cultivate amnesia to – more than just the aridity of the west. The fever dreams of a burgeoning nation-state would draw and push thousands of migrants, most of whom “came from eastern parts of the United States, but a significant number [who] came directly from Germany, Austria-Hungary, Sweden, and other foreign countries”.3 These settlers would go on to bust the sod of the great plains, with the new John Deere plow,4 and they would plant wheat. It is wheat which would fuel British-American industrialization and catapult the U.S. onto the world economic stage, detonating major developments of 20th century food regimes and geopolitics.5 From the frame of reference of the cash-nexus of the industrializing capital east, this prairie was a new and promising commodity frontier a frontier of appropriation6 – but that is a long and wending story for another time. For our purposes, it is this acute historical confluence around the hundredth meridian which is of interest.

In 1881, three years after Powell published his Report on the Lands of the Arid Regions of the United States,7 Elizabeth Demmer arrived in Decatur county with her parents and 4 siblings. They were the vanguard of an early wave of immigrants fleeing the Austro-Hungarian empire, seeking fortune or respite in America. Many of these new immigrants came from the foothills of the alps. Migrants would settle around Lincoln, Nebraska. Or they would spill like floodwaters onto the other side of the border into Decatur, Kansas.8 At the age of 20, Elizabeth would marry George Thir (age 23) and take his name. George had arrived in Decatur County with his folks just 3 years prior and had filed a homestead claim on 65 hectares of what has been referred to as virgin prairie, unbusted sod:

They arrived in an agro-ecological setting in Kansas that had immense potential but little existing structure. There fertile soil was abundant and cheap, labor hard to come by, and rainfall uncertain. Population density was low, and even livestock were in short supply and expensive. George and Elizabeth spent their lives creating a new agro-ecological system where none had existed. They brought labor to bear: their own strong backs plus three children and a barnyard full of animals. They tapped into a rich stockpile of soil nutrients accumulated under native grassland over geological time. They organized a new farm system alongside neighbors from home and from many different parts of the world, one that meshed their cultural inheritance with a semi-arid plains environment. The result was very different from the agricultural world they had left behind. Agricultural systems are coupled human-environment systems.9

We don’t have direct accounts from the Thirs of what their perceptions of, and lives on, the prairie were in those early years, but this was a busy time of new arrivals of people of European descent descending upon the great plains. It was also a time and place which continues to harbor romantic and almost procrustean folk narratives of the blood and soil of American national origin. These romanticized narratives about frontiers, the Oregon trail, cowboys, Indians, sodbusters, tomahawks, loin cloths and noble savages were persistent in my own childhood. Popularized in novels, cinema, and television from my parents’ generation through to some of the epic westerns of my childhood in the 1980s and 90s such as: ‘Last of the Mohicans,’ ‘Far and Away,’ ‘Unforgiven,’ ‘Legends of the Fall,’ and of course ‘Dances with Wolves.’ I loved all those films and was quite swept up in the romance myself as a youth, I was especially swoony and susceptible to the ‘noble savage’ narratives. In the Boy Scouts of America (B.S.A.) there was something of a secret society within the organization, of which I was a member for a while. It was called ‘The Order of the Arrow,’ and while it nominally presented itself as a body for those within Scouting who represented the highest values of the B.S.A. in reality it was just pretext for a bunch of adults – and a few youths – to gather, dress up in Native American-esque garb, bang some drums, chant, and in other words and ways, to appropriate fantastical and mostly ill-founded conceptions of indigeneity, conceptions which gloss over and too quickly move on from the bigger story underneath.

It is within this milieu in which I would like to place – at least adjacently – Wilella Sibert Cather, better known as Willa Cather. Nine-year-old Willa would arrive in the Kansas-Nebraska interfluve in 1882, about one year after the young Elizabeth Demmer (soon to be Elizabeth Thir) made her crossing from Austro-Hungary. In the wake of the Kansas-Nebraska act of 1854 – which opened the territory to homesteading and railroad construction – Willa Cather’s family moved from Virginia for many of the same reasons that had compelled the Thir and Demmer families. Whereas Willa Cather never really spent that much time on the 19th century American prairie – though throughout her literary career she would make a lot of hay of what time she did spend there – George and Elizabeth Thir would spend the rest of their lives farming and improving their homestead in Decatur County, growing it from 65 to 260 hectares. Here they would raise their family and live until their deaths in the mid-20th century.10

Cather’s family tried farming in the high lonesome plains but after 18 months moved to the town of Red Cloud and her father began selling real-estate and insurance. After high school, in 1890, Willa Cather would move away to Lincoln, Nebraska to attend University. After University in 1896 she would move to Pittsburgh and then onto New York.11 Willa Cather would have a distinguished career in editing but is best known as a pre-eminent author of early 20th century Plains fiction and even as a forebearer of the environmental movement. She would die in her Manhattan home and be buried in New Hampshire in 1947.

Cather’s fiction gives us a sense of the wide-eyed gaze cast by the settler colonists of the 19th century North American prairie. Something akin to that which young Elizabeth and George Thir may have felt back in 1888 when they embarked on their lives together, lives engaged in work and conversation with the country where they would dwell, farm, and die:

Cautiously I slipped from under the buffalo hide, got up on my knees and peered over the side of the wagon. There seemed to be nothing to see; no fences, no creeks or trees, no hills or fields. If there was a road, I could not make it out in the faint starlight. There was nothing but land: not a country at all, but the material out of which countries are made [my emphasis]. No, there was nothing but land— slightly undulating, I knew, because often our wheels ground against the brake as we went down into a hollow and lurched up again on the other side. I had the feeling that the world was left behind, that we had got over the edge of it, and were outside man’s jurisdiction.

Willl Cather 1954. My Ántonia12

Cather’s romanticization of this place is a tragic reminder of the potency “amnesia” and “blindness”13 hold over the biocultural heritages of precolonial landscapes. The “shifting baselines” of our perspectives regarding landscape ecologies are cultivated through these forces of “amnesia and blindness.” A few seasons of lonely buffalo grass, of growth and decay, can bury a lot. Time and distance, it does not take much of either, to begin to forget; For the language of a taskscape to rust, fade, and decompose – in the same way that so many vernacular languages do.

The Nebraska that Cather describes and which the Thirs settled was deeply clouded with this amnesia – to the peoples and situated knowledges that came before. We can perhaps therefore forgive them their blindness. What is harder to forgive is the continuation of these narratives in the 21st century, the perpetuation of myths when built on intentional blindness to the biological and human histories of the prairie is willful amnesia of our environmental histories. Cather’s texts are rightfully prominent in the cannon of popular American fiction, if brought into conversation and contextualization with environmental history, they can provide us with some valuable perspectives from the vantage of the settler colonist during an acutely formative phase of western expansion in the American empire. That this Great American Desert would become the breadbasket and cowranch of the world would have significant impacts on the geopolitics of the 20th century. Cather’s beautiful stories feed incomplete narratives of American origins, central to their incompleteness, is that they continue to be plagued by such romantic prose of the “pristine myth,” of a pure, innocent, even pre-human nature.

What has been clear to geographers, archaeologists, and anthropologists for decades now is that the vision of the prairie over which Willa Cather, Elizabeth Demmer, and George Thir projected their gaze was far from pre-human. It was a landscape which for perhaps 15 thousand years had undergone dynamic interactions of its human and more-than-human forces. Better described as a “taskscape”,14 it had enfolded with fluxes of pre-Columbian migrations, glacial recessions, little ice ages, floods, droughts, and civilizational morphings. For example, the Mississippi rivershed as told by accounts from Hernan DeSoto’s 1539 expedition was a place of extensive and intensive indigenous settlement. This would not be apparent by the time our settler colonists were arriving in the mid-19th century (300 years later). They may have been blind to this history, that what they were encountering was not an untouched wilderness but something perhaps more akin to what one might expect from an ecosystem undergoing an acute and drastic reorganization.

Geographer William Denevan’s influential research on pre-Columbian populations of the Americas, and the taskscapes of its people, offers challenges to the perpetuation of willful amnesia. Despite the slowness with which it has been embraced, work such as his has been essential to the cultivation of narratives which are more grounded in scientific facts, humility, and which can sincerely engage with the complications, challenges, and confluences of historical ecology.

The human impact on environment is not simply a process of increasing change or degradation in response to linear population growth and economic expansion. It is instead interrupted by periods of reversal and ecological rehabilitation as cultures collapse, populations decline, wars occur, and habitats are abandoned. Impacts may be constructive, benign, or degenerative (all subjective concepts), but change is continual at variable rates and in different directions [my emphasis]. Even mild impacts and slow changes are cumulative, and the long-term effects can be dramatic. Is it possible that the thousands of years of human activity before Columbus created more change in the visible landscape than has occurred subsequently with European settlement and resource exploitation?…American flora, fauna, and landscape were slowly Europeanized after 1492, but before that they had already been Indianized. ‘It is upon this imprint that the more familiar Euro-American landscape was grafted, rather than created anew’.15

The Great American Desert encountered by the settler colonist was a landscape(s) of feral proliferations, a response to the introduction of the intentional and unintentional forces of the Columbian exchange. It was its confluence with the pre-Columbian indigenous/endemic forces which by the 17th century had almost exterminated a keystone species, sapiens. Foregrounding the genocide and dispossession of indigenous Americans by European Americans is a massive and fundamental current of our history. A significant part of that work is to foreground our historic and ongoing amnesia with respect to the biocultural heritage and situated knowledges of these taskscapes if we hope to meaningfully cultivate both its new and resurgent vernaculars.

There are some implicit, relevant, and useful ironies in attempting to employ such an unwieldy analogy as river currents – or hydrology in general – as a framework towards the cultivation of both new and resurgent historical-political vernaculars. Despite those ironies, I suggest that the effort is worthwhile. Because while it can be insightful to try and separate the particulate dynamic of any given current or eddy from the holism of the watershed, as an explanatory model it is also perilously reductive. For example, the term ‘watershed moment’ is misleading, when exactly does a ‘watershed moment’ occur? Is it a grain of sand that gets blown by a Pleistocene gust of air? A batholithic uplift pursuant to magmatic thrust? Where would one reduce and locate the complex of resistance to that uplift? Thankfully it is not the point of this paper to catalogue the upending insights – and at times confounding perspectives – that a half-century of environmental histories have opened to us. Rather, we might look to the recently published book, The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity, written by anthropologist David Graeber and archaeologist David Wengrow for such review and synthesis.16 My aim in this essay is to point towards the vital processes – human, and more-than-human, such as the hydro/glacial dynamics that extensively which shaped the Great American Desert. These are inspiring analogies and frames of reference through which to view our environmental histories. The glacial till left by the Wisconsin glaciation is the fertile North American steppe upon which Willa Cather and the Thirs arrived in the mid-19th century. The processes which contoured their material and ideological watersheds is the big story of their political and historical ecology. Furthermore, these processes have continuities through to the 21st century. I will return to this conceit of ‘the big story’ below, after telling an even bigger story

Part 2

Vernacular Chattermarks

(Or Processual Entanglements and a Scotch on the Rocks)

Glaciated landscapes are especially adept at dilating temporal perspectives, I have had the great privilege to spend some quiet and extended periods in those of Norway and Alaska. The glacial activity which exists in those terrains today is impressive but is dwarfed by the geological record of twenty thousand years ago. During that period global glaciation was experiencing what is now called the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), and while it was a low-water mark for ocean levels, the LGM was something like the high-water mark of our current ice age, with planetary ice sheets more than 12,000 feet thick.

Spurring off the Fennoscandian ice sheet, one especially raspy glacier was carving out the Konge of the Norwegian fjords (The Sognefjord). As a result of that sculptor, the bedrock of the Sognefjord in the 21st century now lies 4,900 feet below sea level. Back when its kind ruled the north, the glacier that flowed out of the Sognefjord was 10,000 feet thick, 3.7 miles wide, and 62 miles long. Under this kind of pressure ice becomes dynamic, fluid-like. It moves like a river in slow motion. Glaciologists call this ice ‘plasticized.’

To understand what it takes to become a fjord, imagine that you begin as one of these Pleistocene rivers of plasticized ice churning to the sea, a single watershed flowing off a continent of ice. Your body moves and bends like a river – with all the attendant currents, eddies, and cascades – not to mention an insatiable erosive appetite. Your existence is the slow groaning and inaudible grinding of stone and ice for ten or twenty thousand years. Your world is never static.

When I was a kayak guide in southcentral Alaska, we paddled through little bergy bits of ice which calved off Aialik glacier into the bay. The glacier had a remarkable flow rate of about 2 feet/day. While the Aialik glacial watershed itself – like the watershed of any ancient river – is tens of thousands of years old, much of the denser, clearer ice that was outflowing into the bay was estimated to be only about 100 years old. The glacier is to the glacial watershed as is the river to its watershed. Supposedly Heraclitus wrote that no man ever steps in the same river twice, the water of a river is fresh, likely from recent rain and snow melt, seasonal and lively, its movements and currents are events that are over in an instant. The watershed itself is also dynamic and subject to seasonal events, but its changes have taken place for millions of years and are a stitched and eroded patchwork of forces echoing through the tectonics of deep time. When I was bobbing around one especially memorable evening in the 100-year-old cocktail ice of Aialik bay, I was struck by the realization that my grandfather (the same age as that ice) was at that moment probably in the process of pouring himself his favorite aperitif, a Scotch whisky on the rocks. Thinking on him and holding a bit of it in my hands, my memory, did not feel so much like mine alone. Its capacity and form was not delimited by the spatial-temporal frame of my normative neuro-corporeal machine. It was more like memory was sensations: it was affection for my grandfather, understandings of glacial geo-stories, and presence. It was an intimate encounter with entanglement on multiple spatial and temporal scales. In a sense I experienced continuity through this taskscape, but perhaps it would be better to understand what I am describing as the taskscape ourself. It was as if I could not only think of my grandfather but almost remember him, remember him as a newborn baby in the winter of 1916. The winter of his birth, snowflakes fell on the Harding Icefield high above Aialik bay. Flakes that were destined to become glacial ice and flow to me 100 years later. Glacial ice, like a landscape, is nothing more than the congealed instant of its taskscape, melting into its next scape. But what is that nothing more? What is the instant of its taskscape?

A brick-sized block of brash ice is composed of thousands of bygone snowflakes. Its taskscape, the process of multiple Gulf of Alaska storms and snow dumps, cool summers, high humidties, resistance to shale or slate, granite, gneiss, or basalt bedrock, and the compression forces these variables allow. As it turns out, the taskscape of a piece of glacial ice can also be of melting in the hands of a distracted kayak guide, and memories of his grandfather.

When snowflakes are compressed to the point at which they become glacially liquid, it becomes a bit absurd and inaccurate to try and atomize them again. Glaciers are anything but monolithic, they are as dynamic as the currents and particles of a river, they too change as the watershed. To atomize our histories also tells an incomplete story. So, what I am flailing at here is how to consider process as a premise – even ontology – of our historiography, not just an aspect?

Processual or durational – rather than completed – narratives might humble, ground, and substantiate our ways of knowing by merging the constituent human and more-than-human memories embodied in a landscape culture. Can we resist categorical versions of time which risk ignoring dynamic currents of the temporal-spatial-historical-cultural-biological processes? Perhaps there are some helpful touchstones in these flows as we attempt to network temporal and spatial ways of knowing. Process is a useful touchstone, imagine touching a stone, and imagine countless others doing the same, patina is a process that can involve human actors, but it always involves more-than-human actors and time.

Environmental histories are grasping at ways of knowing and telling which resist reduction of narratives to the unidirectional, steady, causal, anthropocentric march of time and matter. On the other hand, environmental histories – most storytelling – also palpate at sets of relations and patterns, even big patterns. This terrain can be fraught with the pitfalls of teleology and hubris. Confronting this challenge and borrowing from the trans-disciplinary anthropologist James Clifford, Donna Haraway deploys the concept of ‘big enough stories.’ These are stories which invite into themselves a multiplicity of tricksters. These would be stories that engage open-endedness’ potential to cultivate narrative landscapes rooted in humble and palpable ways of knowing. Rather than viewing our world as more or less finished, one in which all the main essences have already been assembled and are now just being deployed in a few and limited configurations towards inevitable progress and eventual apocalypse, open ended stories acknowledge the “ongoingness” of “geostories”.17 ‘Big enough stories’ focus on the affection that human and more-than-human vitalities – I will call those things earthlings for now – sense in one another. Affection draws earthlings towards one another, and forces them into dialogue, negotiation, entanglements, and novel becomings.

Nowadays something like 90% of plant species on earth use flowers as a mechanism. The emergence of flowering plants was a series of events which precipitated a Cambrian-esque explosion of earthlings, but the capacity to flower was at some point a novel emergence in the geostory. Their’s is a geostory which is clustered around the terrestrial vegetal organisms, but one whose emergence is more completely understood as an entangled becoming. In that it has involved relations and proliferations of actors at both the cellular level and of the creeping, crawling, and winged pollinators.

If I could, I’d like to unstick time a bit, cast a spell of floral amnesia, and plop the old taxonomer Carl Linnaeus and the tricksy Kurt Vonnegut back in the early Carboniferous period 300 million years ago for some dialogue and speculation. It seems unlikely that either of their creative and scientific minds would have predictively imagined the coming emergence of flowers into the geostory. Moreover, it is most interesting of what their imaginations might have instead speculated at in that muggy horsetail fern landscape of unknown potentials. What happens when we start considering our geostory as one of ‘ongoingness?’ Apricot orchards are planted in the till of receding glaciers, guano builds and flowers bloom on the scoured and uncovered stones. What imaginations and becomings emerge when we view our geostory not as finished but merely at the dawn of creation? Around what might some of the coming flowerings cluster?

Environmental histories tell entangling stories in resistance to those which divide earthlings, the misleading divisions of nature and culture for example. They offer alternate perspectives to the structurations which shutdown the earthly brainstorms of ongoingness, they are imaginations of potential flowerings. Tools of reduction and taxonomy are useful, but when they feed the politics and ideologies of deterministic narratives, they seem not only to be woefully inaccurate as geostories, but also little more than attempts at disentangling the most vital of relationships between earthlings. In the coming narratives, we can and should identify and talk about the human vitalities at play, we can and should draw hope for resilience and regenesis from them. But those moments when we can dissolve the boundaries between human vitalities and the more-than-human vitalities, through our ways of knowing, are precisely the places at which we might draw the most hope. For in those places, it is not just a play of vitalities, but rather a constant becoming of those vitalities, a sensation that our so-called human vitalities do not exist separate from the vitalities of the more-than-human. In that kind of narrative, we might appreciate that ours is hitched to massive and potent forces of resurgence and creative emergence.